Reading Wendell Berry in Berea, KY

November 11, 2008

A few days after we voted Barack Obama into office, I found myself in Berea, Kentucky. Joan’s father is from Bimble, Kentucky (or as he says in the title of his memoir, “The End of the Road at Bimble, KY), and we were driving him around for a few days to visit some old haunts. One of those was Berea, a town that’s pretty much wrapped itself around a fine little liberal arts college called Berea College. People familiar with the world of fine crafts probably have heard of the place, but for my money what’s more remarkable is that the college is one of the oldest incarnations of true radicalism that you can find in the US of A. Think back to 1855, and think of some missionary types founding a college in southeastern Kentucky that would be tuition free and would serve the children of Appalachia. Including blacks. And think of what it was to try to run a college founded on anti-slavery and egalitarian principles in a slave state just a few years before the Civil War. The college was run out of town by 1859 but its founders returned in 1865 at the end of the war, a rather impressive example of stubborn commitment to a good and important idea. The race problem would continue to dog the college for the next century, but it has held more or less true to its founding mission, still providing an education for kids who are smart enough to get in, and still paying tuition for those who can’t afford it. I talked with one young woman who has a half dozen brothers, and whose parents had no education beyond grade school (mother) and high school (father). She’s a dual major in chem and biology and wants to be a doctor. On the other hand, another student told me she’s quitting the college. It’s not a good fit for her. I sat in a smoker’s gazebo on campus, reading a from Wendell Berry’s book of essays published in 1991: Sex, Economy, Freedom and Community, while other students dropped in, seeking a bit of protection from the cold rain, and the opportunity to smoke in a college -sanctioned spot. Read the rest of this entry »

To eat, or not to eat

August 14, 2008

This wet summer has soaked the ground and brought the mushrooms up, as many shrooms as we can remember in the half-dozen years we’ve been hunting and gathering them. We eat some 15 varieties that we’ve become familiar with, brands we know with certainty are tasty and benign. Black trumpet, hedgehog, painted sullius, blewit, oyster, bear’s head tooth, ash bolete, chanterelle, hen-of-the-woods, cauliflower, giant puffball, berkeley polypore, morel, and a few others. A few weeks ago we discovered a new prospect, American Caesar’s, an orange mushroom with a red nipple on its head that blooms up first as a bright red ball. It’s of the Amanita family, that bunch of mushrooms that brings you such scary characters as Fly Agaric and Destroying Angel. Interesting company for an edible mushroom to keep. Particularly because Caesar’s has a look-alike which will make you very very sick. But if you know what to look for, identifying the American Caesar’s mushroom with certainty is no problem. So why have I resisted doing that first taste test? (No matter that you are certain of a mushroom’s identity…you MUST always do a trial tasting test, eating just a half of the cap and waiting 24 hours…). The beautiful American Caesar’s, the promise of a tasty new mushroom, and, uh, the very, very low risk of mistaken identity. I’ve been stalling for weeks. Then I read about a world class expert on mushrooms who says, “I never eat Amanitas, period. Never.” To live is to manage risk, to balance the probable against the improbable. I like risk, and can accept more than most people, I think. However, just two days ago I decided to defer to the wisdom of somebody who thinks about the risks of having some mushroom toxin dissolve his liver…it ain’t worth the chance. The taste, that is. So I have adopted that rule. I don’t…do not…eat Amanitas.

This wet summer has soaked the ground and brought the mushrooms up, as many shrooms as we can remember in the half-dozen years we’ve been hunting and gathering them. We eat some 15 varieties that we’ve become familiar with, brands we know with certainty are tasty and benign. Black trumpet, hedgehog, painted sullius, blewit, oyster, bear’s head tooth, ash bolete, chanterelle, hen-of-the-woods, cauliflower, giant puffball, berkeley polypore, morel, and a few others. A few weeks ago we discovered a new prospect, American Caesar’s, an orange mushroom with a red nipple on its head that blooms up first as a bright red ball. It’s of the Amanita family, that bunch of mushrooms that brings you such scary characters as Fly Agaric and Destroying Angel. Interesting company for an edible mushroom to keep. Particularly because Caesar’s has a look-alike which will make you very very sick. But if you know what to look for, identifying the American Caesar’s mushroom with certainty is no problem. So why have I resisted doing that first taste test? (No matter that you are certain of a mushroom’s identity…you MUST always do a trial tasting test, eating just a half of the cap and waiting 24 hours…). The beautiful American Caesar’s, the promise of a tasty new mushroom, and, uh, the very, very low risk of mistaken identity. I’ve been stalling for weeks. Then I read about a world class expert on mushrooms who says, “I never eat Amanitas, period. Never.” To live is to manage risk, to balance the probable against the improbable. I like risk, and can accept more than most people, I think. However, just two days ago I decided to defer to the wisdom of somebody who thinks about the risks of having some mushroom toxin dissolve his liver…it ain’t worth the chance. The taste, that is. So I have adopted that rule. I don’t…do not…eat Amanitas.

Getting just a bit away

August 10, 2008

One of the first of many minor pleasures that Joan and I began practicing some 25 years ago when the kids were still small was state parking. As in quick camping trips to a couple of choice local parks. Joan discovered our favorites early on, and Pillsbury State Park in E. Washington is probably at the top of the list. It’s about 45 minutes from Warner, and you drive down through the back end of Bradford, along a road through a wetlands that for some reason used to give me the creeps…a little too low, a little too dark…a little too, uh, creepy. But it doesn’t anymore. Give me the creeps, that is. Probably because in the intervening 25 years I’ve found quite a bit more in the real world that is sufficient to give me the creeps for real reasons, and I’ve let the imaginary ones fade. Pillsbury is on the state Greenway, a hiking trail from Sunappee on down to, I dunno, but I’m sure it stops short of the Mass border. For what it’s worth (and it’s worth a lot…because the state of NH in its wisdom has decided to charge a premium for the privilege of camping in its campgrounds), there is nothing finer, if you’re in the mood, than a couple of nights on the little lake, listening to the pair of loons, watching the rays of the rising sun come through ropes of mist rising from the water, sipping coffee and wondering why the heck you don’t do this more often when it’s so close and easy.

Journal de Costa Rica: 27.Feb.2008

February 27, 2008

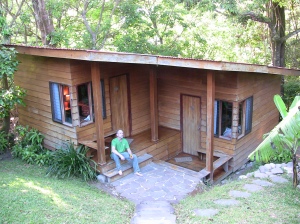

Arco Iris Lodge, Santa Elena/Monteverde

N 09.93081 W 084.06044

Seven a.m. Sitting at a table on the lawn outside the little lodge at Arco Iris. The ten cottages of this place are scattered in a rough circle around the lodge, stepped into the hillside. Sunlight just coming over the hill brings out the deep golden browns in the exterior walls of the cabins. Several small orange trees are blooming, and their fragrance drifts on the breeze. It is cool, cool enough to wear a long-sleeved shirt. There is a small stand of banana trees, a tiny thicket of bamboo, but I cannot name any of the other trees. Looking out over the valley to the south, I can almost see the ocean 30 km away on the this side of the Golfo de Nicoya.

About five a.m a hundred different birds began to call, but an hour later the hills came alive with the snarls of dozens of small two-stroke motorcyles as workers head for their jobs. By seven, the roar of earthmoving machines from the hillside nearby drowns the songs of all but the closest birds. I ask the Costa Rican woman who manages the front desk here what’s being built. She makes a wry face. Doesn’t really know. Thinks it may be a shopping mall. I know it is, because I’ve already asked other people. The site of the mall is now a wide, treeless, red gash on the hill.

The day before yesterday we visited the orchid garden that is just next to the lodge. Nearly 150 varieties, all wild, but not all from Costa Rica, are in bloom. Our guide was Stephania, a young Tica (Costa Rican woman). She grew up in Monteverde, and learned her perfect english at a private school here, which might have been (I forgot to ask her) the Esquela des Amigos, a school run by the Quakers, who came here more than a hundred years ago and began dairying and cheesemaking. Los Cuaceros. Stephania tells us about the pollination strategies of orchids (some change color after pollination, others drop their lower petal), gives us spanish lessons, and tells us that she would love to work as a guide and spanish teacher for gringos who visit. I take her name and email. A highway of leafcutter ants runs over the path at our feet as we talk. Lorita, the resident parrot in the orchid garden, grumbles in the thick foliage of the short trees that shade the garden.

As I write these words, a single parrot flies overhead, flashing red and green, squawking. A pair of small birds with iridescent green wings land in one of the orange trees. White faced monkeys (los monos de cara blanca) swing through the branches of a tree at the windows of the dining room, mugging and begging until the waitress opens the window and hands out a tiny banana, which immediately provokes a vicious, screaming fight and chase.

Yesterday morning a naturalist guide picked us up, with several other guests, early in the morning. We hitched a ride with some folks who had rented an SUV (the roads are pretty raggedy, and four-wheel drive, though not essential, could get you out of trouble) and followed the guide as he rode his motorcycle to the Monteverde forest reserve, several miles away. As we pulled into the parking lot, we saw a woman running with a camera, long lens and tripod bouncing on her shoulder.towards a group of 10 people, all with camera or binoculars, all focused high up on the branches of a tree covered with tiny orange berries or fruits. Our guide ran over to our car, gesturing frantically. “Hurry, hurry! Quetzal!”

A pair of them perched lazily high above our heads, leisurely plucking fruit, more or less oblivious to the straining crowd of humans below and the glitter of lenses focused on them. The quetzals can only be described as replendant. Iriidescent greens and reds and blues, trailing tail feathers a foot long, graceful necks. There are only 150 pairs left in the Monteverde forest.

For the next three hours we hiked the easy paths through the forest. Our guide found hummingbirds sitting in their nests, yellow kneed tarantulas in their burrows, sloths sleeping on branches and told us more than we could possibly remember about other fauna and the plants and trees of this cloud forest. Towards the end of the walk he stopped at a wide point on the trail and gave an impassioned speech about how he has seen Monteverde change…for the worse…during his life here. He pleaded with us to do something…to plant a tree before we leave. He said he feels he could kill the lumbermen who have cut so much down. I filmed him making that speech, and will edit it into a mini-doc and send him DVDs of it that he can use in presentations. He has been to the US twice he said, to talk about Monteverde.

We spent the rest of the day hiking much rougher paths, climbing high enough to see clearly the Nicoya Peninsula, and the Isla de Chira lying in the waters of the gulf, where we will be Friday evening.

We rode the local bus back to Santa Elena, stopping every eighth of a mile to drop off or pick up passengers. At one stop, near the stop for the Escuela des Amiigos, a ten-year-old boy climbed on, carrying a small book bag and sucking a lollipop. He sat quite purposefully next me. After a minute or two I said, “Buenas.” He looked me in the eye, rolled his lollipop, and without removing it, said “I do speak english you know.” So for the next five minutes I had him give me some spanish lessons, which he delivered with the pacing of a seasoned teacher. And then, out of nowhere, he said, “I have never seen a quetzal.” I was taken aback. I had not mentioned the quetzals we’d seen that morning. Was the word already around that the tourists had seen quetzals at Monteverde? I don’t know. It was our stop. I thanked him for his lessons, and told him I was certain he would soon seen see a quetzal.